Alaska History & Culture

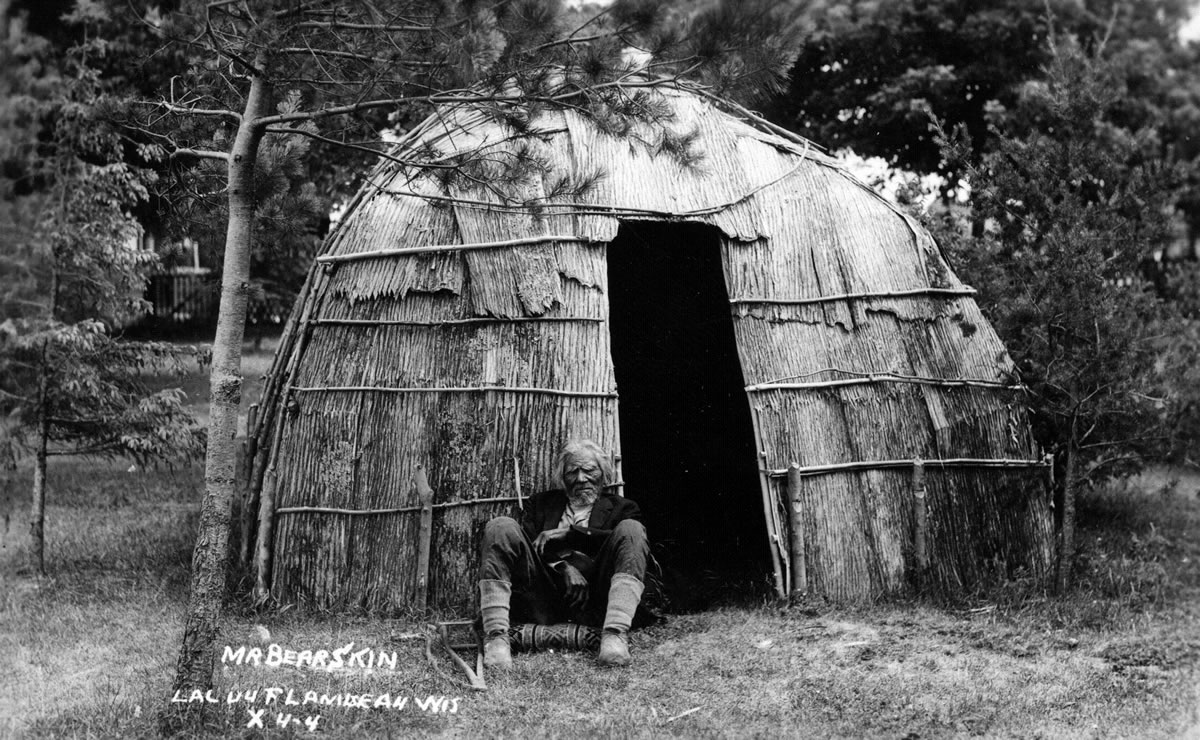

pokegama lake lodge

The Alaska Frontier and NorthWest Coast Native American Culture

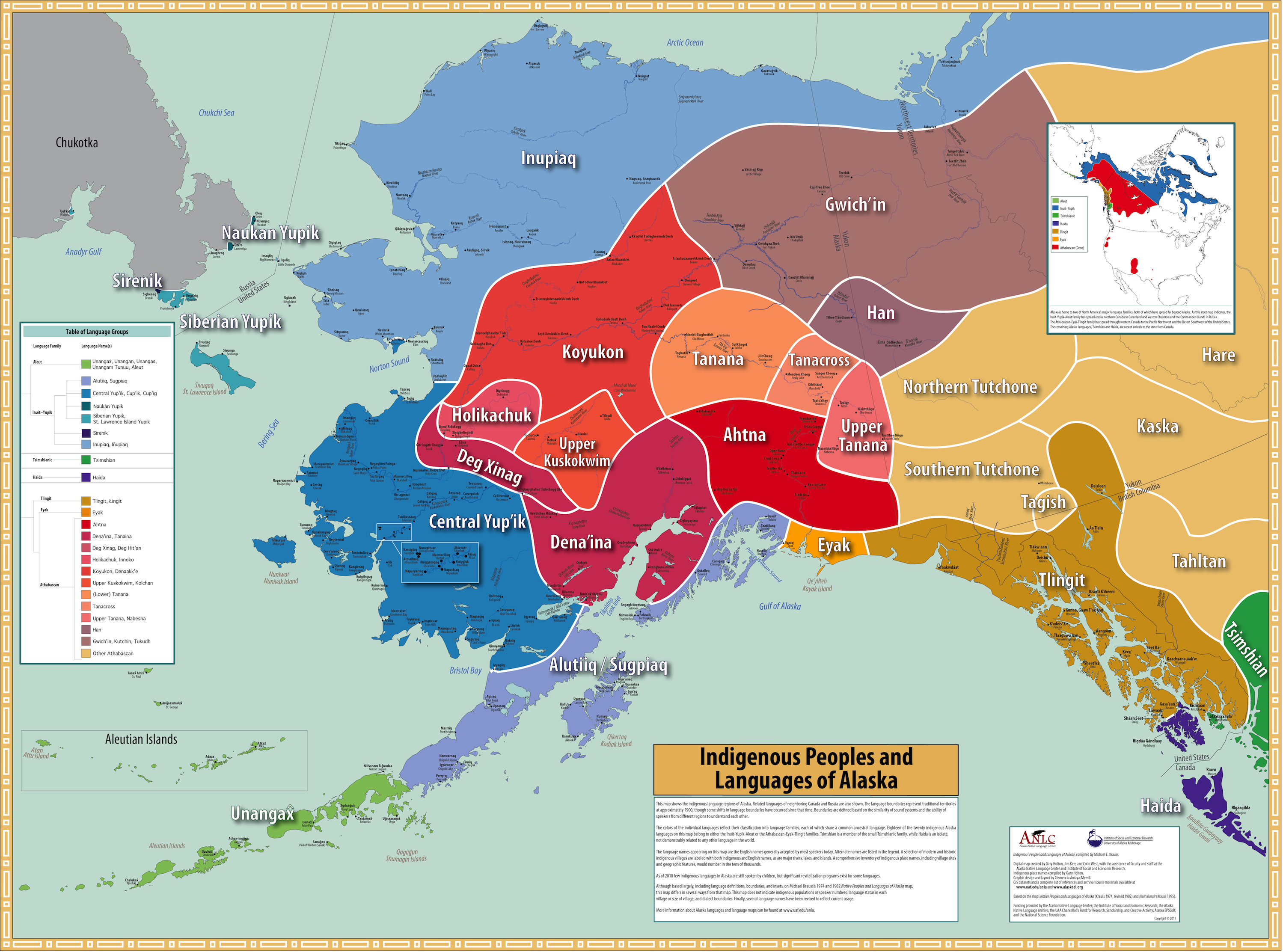

The history of the origins of Alaska and the Northwest Coast, is extensive and significant. Approximately 10,000 years ago, inhabitants began settling along North America’s Northwest Coast after traversing the land bridge in the Bering Sea from Europe. By 3,000 B.C., communities had established permanent villages along the region’s rivers, peninsulas, and islands.

Alaska The "Last Frontier"

“The Last Frontier,” a phrase prominently displayed on Alaska license plates, signifies a cultural narrative integral to Alaskan identity. One hundred and fifty years ago, the United States acquired Alaska from Russia. Although Russia proposed selling Alaska to the United States in 1859, the impending U.S. Civil War postponed the transaction. Following the war, Secretary of State William Seward promptly pursued a renewed offer from Russia. On March 30, 1867, he reached an agreement with Russian Minister Edouard de Stoeckl to purchase Alaska for $7.2 million.

In Sitka, the capital of Alaska, a unique frontier society was established, rooted in the ideals that resonate deeply within the American consciousness. Following the ratification of the purchase treaty, thirty ships departed from San Francisco bound for Sitka, carrying merchants eager to capitalize on natural resources and military personnel tasked with asserting control over the newly acquired territory.

Americans were cautioned to remain vigilant against Indigenous peoples and to always have “guns charged with grape and canister always bearing on their Sitka (Tlingit) village.” The subsequent events that unfolded following the arrival of settler groups from the United States mirror many historical accounts of American Western “frontier” towns. Land parcels were acquired by companies to leverage Sitka’s boomtown status, saloons emerged along the main street, and tensions escalated between the Indigenous Tlingit and the newly arrived U.S. Army.

Sitka, Alaska, may have appeared isolated from the United States to the numerous settlers arriving post the Treaty of Cession in 1867, yet visualizing Sitka as a frontier town necessitated a considerable leap of imagination. The Russians erected their initial fort on Baranof Island in 1799, and by 1808, they had designated the capital of Russian America at what is now the downtown area of Sitka. Over time, the settlement expanded to incorporate churches, schools, warehouses, bathhouses, retail establishments, a hospital, a sawmill, a foundry, a tannery, a saltery, a shipyard, a laundry, and a seminary.

Historians suggest that Sitka’s moniker, “The Paris of the Pacific,” may trace its origins to the subsequent Russian American period. During a visit to Sitka in the 1830s, Peter Skene Ogden, the chief trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company, famously remarked, “Oh, you really are quite civilized!”

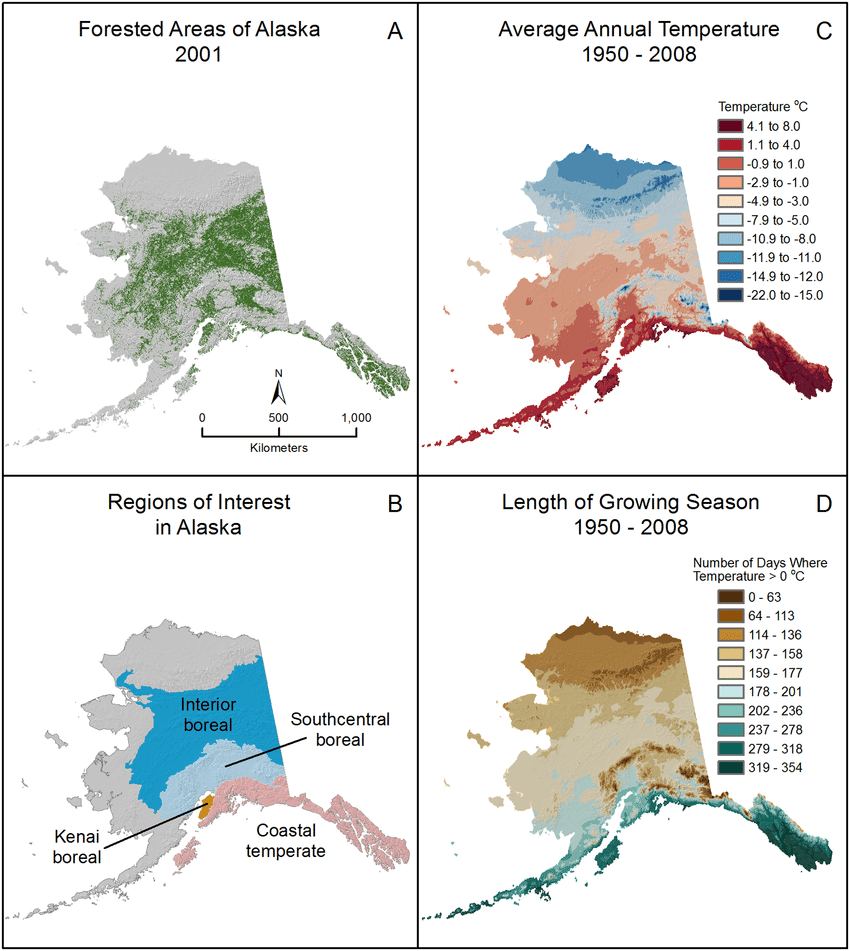

The Alaska Wilderness

Visit Alaska and you’ll see why this state is often referred to as America’s Last Frontier. Expansive landscapes, ancient forests, towering mountains, and rivers abundant with salmon showcase an exceptional and unrefined natural beauty. The pristine wilderness of Alaska serves as a vital habitat for a diverse range of wildlife, including eagles, salmon, caribou, moose, black bears, and grizzly bears. This environment also supports Alaska Natives, who have depended on these lands for their sustenance for millennia.

The wilderness of Alaska holds a distinct status. Over 90% of the land managed by the National Park Service in Alaska enjoys some form of wilderness protection. Under the directives of ANILCA, 33 million acres of Congressionally designated wilderness within Alaska’s parks constitutes approximately 30% of the nation’s total wilderness areas. In conjunction with nearly 18 million acres that are deemed eligible for the National Wilderness Preservation System, Alaska’s NPS wilderness encompasses diverse ecosystems, including watersheds, mountain ranges, glaciers, wetlands, coastlines, volcanoes, tundra, forests, and wild and scenic rivers.

These expansive landscapes facilitate ecosystem-level dynamics, supporting significant phenomena such as mass migrations of caribou and the natural fire disturbances that result in varied vegetation communities. Beyond their ecological value, Alaska’s wilderness areas protect vital cultural resources, serve as living laboratories for scientific inquiry, offer unique recreational experiences, and sustain subsistence resources.

Wilderness areas in Alaska are integral to the homelands of Indigenous peoples, and our current stewardship of these lands honors the deep-rooted connections between communities and their environments. A particularly noteworthy characteristic of Alaska’s wilderness is its provision of opportunities for rural residents to maintain a subsistence lifestyle.

Northwest Coast Culture's

Approximately 8,000 years ago, the first Native American tribes established themselves in the Pacific Northwest after migrating southward from present-day Alaska and Canada. They swiftly acclimated to the temperate coastal climate and utilized large canoes for efficient travel along rivers and coastlines. Renowned for its towering trees, the Pacific Northwest provided ample resources for these tribes. The impressive cedars were capable of being crafted into canoes as long as 70 feet. Canoe travel was the preferred mode of transportation due to the challenges posed by overland travel through dense forests.

In this region, Native American tribes thrived in a wet and mild climate conducive to agriculture and fishing. Many tribes were situated in the areas that now constitute Oregon and Washington, as well as northern California. Along the coastline, these tribes heavily depended on Pacific salmon as a food source. Among all the regions in the United States, the Pacific Northwest was the last to undergo exploration by Europeans. The Spanish began their northern expansion from Mexico and southern California in the mid-1770s, coinciding with Russian explorations moving south from present-day Alaska. Tragically, similar to other Native American populations, the tribes of the Pacific Northwest suffered devastating losses due to smallpox introduced by European explorers.

In addition to enabling the crafting of substantial and intricate canoes, the towering trees of the Pacific Northwest possessed fibrous roots and inner bark that were suitable for basket weaving. Lumber could be obtained from living trees, and the bark was valued for its medicinal properties. Due to the abundance of high-quality timber that exhibited remarkable durability attributed to its natural insect-repelling qualities, Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest gained a reputation for exceptional wood carving skills, notably in the creation of totem poles in the northern regions.

The First Nations tribes of the Pacific Northwest created large and ornate totem poles to convey narratives and commemorate significant events. Similar to the lengthy canoes, totem poles could reach heights exceeding sixty feet. The tallest poles were typically erected as memorials. The period of totem pole creation peaked in the early 1800s, coinciding with European contact and the introduction of tools that facilitated more intricate carvings. The process of carving a totem pole was regarded as a solemn endeavor, and traditionally, only men were permitted to undertake this craft until the modern era.

For over 10,000 years, the Native peoples of the Northwest Coast have contributed significantly to their communities through trade. Spanning from Yakutat Bay in Alaska to the Columbia River in Washington state, Indigenous fishermen and maritime hunters navigated the waterways north and south, as well as eastward into the interior via mountain passes, to exchange valuable commodities such as oolichan oil, dentalium shells, copper, and mountain goat wool.

In a region abundant with natural resources, this trading economy fostered the development of comfortable and sophisticated societies characterized by social stratification, elaborate ceremonial practices, and exceptional artistic expressions that celebrated the heritage and prominence of families, clans, and lineages.

During feasts, or potlatches—a term derived from the region’s trading jargon—the status of notable families was affirmed through their generosity toward guests. By bestowing lavish gifts of essential goods and luxuries—including, later on, non-Native trade items—communities effectively shared their wealth and sustained social equilibrium.